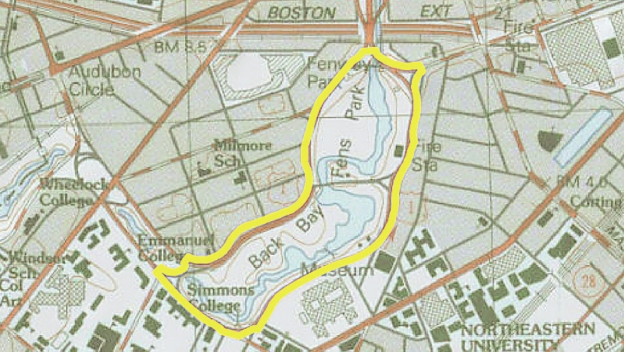

New pathways, drainage systems, and more accessible routes to monuments and memorials are coming to the Back Bay Fens this year through the Pathways Project, introduced by the Parks Department.

Filed in July and reviewed by the Conservation Commission this past month, the project has been years in the making and will build upon the 2023 completion of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineer’s multi-phased, Muddy River Restoration project that focused on flood mitigation and reconstruction and replanting of the banks along the river.

The two-year long project will lead to specific areas and paths to be shut down momentarily from Avenue Louis Pasteur to Boylston Street to install gravel walkways with “ADA-compliant” asphalt, plant new trees, and add infiltration trenches and areas for stormwater drainage.

To capture rain runoff and prevent flooding, there will be stone covered perforated pipes, which will allow water to slowly drain to prevent overflowing groundwater.

Parks and Open Space Committee of the Fenway Civic Association (FCA) board member, Freddie Veikley, says it's their hope that the project keeps the park pedestrian-focused, and will allow for easier enjoyment of the historic area.

She says other agencies’ work, including the Muddy River Restoration and the FCA’s upcoming upgrading of the John Boyle O'Reilly Memorial statue have worked together to “have a collective effect” on the entire area.

“The Parks Department's role is more interior to the Back Bay Fens and the other things that go along with not just the pathway renewal, but also the drainage, some of the park furniture, and making the areas accessible, " Veikley said.

However, not everyone is excited about the specifics of the project. Caroline Reeves, an associate researcher at Harvard University and one of the founders of the Muddy River Initiative, says that while she thinks the project itself is needed, the materials being used are dated. Instead, she says the city should be looking at permeable materials as they did for City Hall Plaza in 2023, which allows water to drain through the materials. Whereas, impermeable surfaces, like asphalt, lead to runoff.

One of the biggest downsides to using permeable surfaces is that they require maintenance, and in turn, more of an economic investment and time. The latter of which both Reeves and Veikley says is likely the reason behind choosing asphalt for the paths. “Let's not use yesterday's technology when tomorrow's technology is already here today,” Reeves said. “Boston parks is doing a great job, but we as a city need to start thinking in terms of maintaining what we have and using better technology, because that's going to get us from a hopeless environmental profile to a much more hopeful future for our young people.”

As of early September, the project was still in the design phase with Kyle Zick Landscape Architecture consulting and has a reported budget of around $6.5 million.