For more than 75 years of its nearly 100-year existence, the National Braille Press (NBP) has been shaping literacy for the visually impaired from its Fenway neighborhood home.

After purchasing the building at 88 Saint Stephen Street in the late 1940s, the nonprofit expanded from a weekly Braille newspaper to a national Braille printing press for textbooks, literature by blind authors, and materials for public signage and private businesses.

Today, the NBP continues to expand its mission by spreading Braille literacy education, providing requested reading materials, awarding an annual Touch of Genius Prize for technology for the visually impaired, and advising public and private institutions on Braille translation and application.

Braille reading materials can cost three times as much to produce as their non-Braille equivalent. This can leave visually impaired children at a serious disadvantage in their early education.

When confronted with the costs of Braille materials, many educators and policymakers turn to audio tools, which Joseph Quintanilla, a vice president of the NBP, said are a poor substitute.

“I’ve been blind since birth, but I did have some usable vision. So, unfortunately, I thought I had enough vision to push away Braille and try to read with the limited sight that I had. It wasn’t until the latter days of high school when I realized that was a mistake,” Quintanilla said in an interview.

“My writing suffered, not being able to really read. We speak a little differently than we write, so I had to re-teach myself to write, which limited myself in the opportunities I could’ve had,” he continued. “I was excited to come and work at the NBP because of the programs it has for children and parents, to educate them about the important difference between reading and listening.”

Using funding garnered from individual donations, private grants and fundraising events, the NBP seeks to provide Braille education materials to students around the country at little to no personal cost.

Students can search the online catalog for Braille versions of their textbooks and even request new Braille translations of textbooks and tests. The NBP also helps students receive financial assistance for those materials through their university disability offices.

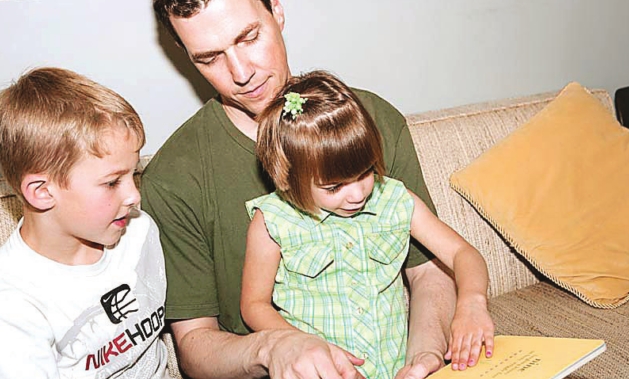

Quintanilla also pointed to the expanding Children’s Braille Book Club, which provides free monthly children’s books to registered families, as a recent success. Over the past 5 years, the program has grown from 125 families to 325, meeting its funding goal of providing free books to every family who requested them. “Would you want your children to go through school just listening? No? Well, blind children shouldn’t go through that either,” Quintanilla said.

The NBP is a national organization, but its longtime home in Fenway has amplified its local reach. The greatest percentage of Braille readers served by the press is in Massachusetts. Last year, the Mission Hill Fenway Neighborhood Trust donated $5,000 to the Children’s Braille Book Club to fill local subscriptions.

Quintanilla said the Fenway location has also been a natural fit for the needs of the press’s own visually impaired employees, who make up about 30% of the around 40 employees, due to Boston’s accessible public transit and Fenway’s central location.

While the cost of materials and the lack of government funding make fundraising an ever-present need, Quintanilla pointed to societal challenges as the biggest obstacle to the NBP’s mission.

“I personally feel people with disabilities are an afterthought when it comes to inclusion,” he said. “[For example], ADA signage, it’s almost like ‘we’re required to do it,’ but they don’t do it correctly. Sure, a general printer can do it, but they don’t know if it’s being done correctly or not. Blind people are real customers, real students. Real access is important to all these things in life.”